“There is no more important vineyard district in California, all things considered, than that which lies around the old Mission San Jose. …The best wine vineyards are around the Mission and Warm Springs, and on the roads to Irvington and Niles -in other words -on the spurs of the great mountain that rises above the district.” –Charles Howard Shinn, 1889

By Ralph de Unamuno

After having lived in Los Angeles for nearly a decade, I returned to the Bay Area to teach Chicano Studies & History at local community colleges. My commute took me past the Gallegos-Palmdale Winery ruins. My curiosity as a historian led me to research the past of the ruins I had once explored as a young boy growing up in Fremont. I soon uncovered an amazing story about the Gallegos- Palmdale winery in particular, and that Fremont had a remarkable viticultural and enological past in general. From the Spanish-Mission era up to Prohibition, south Fremont (then called the Washington Township), had once been one of the first and most productive wine regions in California. While the Gallegos-Palmdale Winery was not the first or the last winery in Fremont, it is a symbol of a bygone era of Fremont’s historic agricultural past. A past that is all but forgotten but much deserving of acknowledgment to the history of California viticulture and enology.

Figure 1 Ruins of the Palmdale Winery. Photo Credit: The Wine Institute

The origins of the Golden State’s wine industry has its roots in the Spanish colonial era. Wine production began in the late 18th century within the Mission system. The vineyards of Mission San Jose were productive from 1797 to 1836. After the secularization of the Missions by the Mexican government in the 1830’s, the Mission’s vineyards were sold-off and focused on non-ecclesiastical wine markets. In 1849, an early Anglo-American traveler named Bayard Taylor wrote, “A Frenchmen named Vigne made 100 barrels of wine from a vineyard of about six-acres at Mission San Jose.” In the early days U.S. occupation of California, Anglo-American settlers would plant vineyards and import French cuttings from throughout Europe. In 1862, J.C. Palmer imported from France and Spain 10,000 cuttings of various varietals. In this era the vines of what would become the California heritage wine, Zinfandel, would also be introduced to the area. By the turn of the century southern Alameda county would have earned an international reputation for its wine and vines.

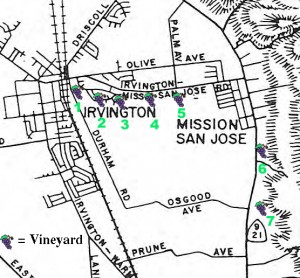

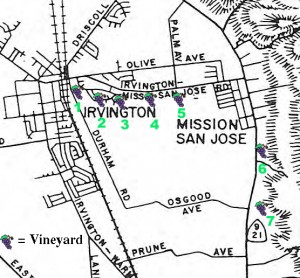

By 1893, the present-day districts of Mission San Jose and Irvington had 1,627 acres of vineyards under production. These vineyards grew 5,092 tons of grapes, and the wineries produced 2,058,800 gallons of wine. Interestingly enough, what could be seen as the equivalent to a little “Silverado Trail” by 1893 standards along the well-traveled thoroughfare of Washington Boulevard leading up the hill from the Irvington district to the Mission San Jose. Traveling east past present-day Driscoll/Osgood road along Washington Boulevard would take you smack dab in the middle of the historic wine country of southern Alameda county. If 1893 was the early historic high-water mark, the world-wide phylloxera infestation of the 1890’s would be its historic low point.

Figure 2: Map of Washington Township Wineries. Key: 1. Beard/Gallegos/ Palmdale Winery; 2. Grau-Werner (Los Amigos); 3. Rosa Bez; 4. DeVaux; 5. Riehr Winery; 6. McIver/Linda Vista Winery; and 7. Stanford/Weibel Winery.

Like the rest of the wine world, the recovery from the world-wide phylloxera epidemic would be slow in southern Alameda county, but further exacerbated by scourge of Prohibition. Wine production after the repeal of the 18th Amendment was further delayed due to the agricultural demands on the home front for World War II. National and international politics aside, at mid-century the future looked bright for southern Alameda County’s wine country. Mission San Jose and Irvington wineries and vineyards would soon reclaim their place in California’s wine industry.

In 1948, the legendary Frank Schoonmaker of Gourmet Magazine touted the region’s past, and what was then seen as a promising future, by prophesying

“There are vines, too, off east of the Bay on the low hills round Mission San Jose…already famous for the excellence of its vintages in the 1850s; and if we are ever to have wines in America that can honestly be called “great,” this is assuredly one of the districts from which they will come.”

From the Livermore valley to the Santa Cruz Mountains, the future looked promising for Bay Area wine in the eye of Schoonmaker. During the early days of the “repeal,” San Joaquin Valley wine producers flooded the market with subpar wine made from table grapes. Local wine makers in Fremont resisted the quick bucks and focused on developing quality wine for the consumer. Robert Maylock of the Los Amigos winery was one of the first in the state to plant Pino Noir in 1943, and later experiment by planting Cabernet Sauvignon in 1945. Los Amigos won sixty medals, one gold for Zinfandel and an honorable mention for sherry at the state fair. It seemed like a given the area would rebound, however history certainly has a way of playing dirty tricks on the future.

The Gallegos-Palmdale Winery ruins that captivated my attention as a boy, and later as an adult, I would soon uncover had an amazing history. The origins begin with two of the early Anglo-American emigrants to what would later be called the Washington Township, E.L. Beard and John Horner. The two purchased 30,000 acres of Mission San Jose Land in 1850. A year later Beard bought out Horner and planted a new vineyard that he would operate from 1851 – 1881. In 1881, Juan Gallegos, an immigrant from Costa Rica, purchased the estate and would soon raise the profile of the area wineries like no other producer. No doubt he would become the first Central American wine maker in California history. Gallegos would build a garden estate near the old Mission, as well as a palatial brick winery and distillery. The Gallegos Winery and Distillery was one of he first gravity-fed wineries in the state, man-made cave cellars, and its own cooperage. From the Mission Era through the late 19th century, the Latino presence in wine making would be represented in southern Alameda County.

Figure 3 The Gallegos- Palmdale Winery. Photo Credit The Wine Institute

Gallegos would later sell the estate to his brother-in-law, Carlos Montealeagre, in 1892. Montealeagre would then sell the winery to the Palmdale Corporation, of which he and his family had controlling interest. By 1893, the Palmdale Company had 600 acres of vineyards with a total annual production of 2,400 tons of grapes, and over 1,250,000 gallons in cooperage. At one time the Gallegos Winery had the second largest wine cellar in California. The Palmdale Winery would change hands once more before its ultimate demise and destruction on April 18th, 1906. The earthquake that would decimate San Francisco would also show little impunity for the Palmdale Winery and Distillery.

Figure 4 East-side of the Gallegos- Palmdale winery.

So why didn’t Fremont become the next Napa, Sonoma, or even an up and coming Paso Robles? The answer lays all around in the blocks and blocks of houses, and the absences of blocks of vines. The wineries of southern Alameda county have long since been plowed under for subdivisions. The rapid suburbanization of the Bay Area in the Post-war era provided too much in the way of economic opportunity in terms of land sales for later generations of area agricultural and ranching families. Now all that remains of the bygone wine past are the cookie-cutter housing developments that now comprise Mission San Jose and Irvington. The lackluster demise of Fremont’s wine industry came to a definitive end in 1996, when sparkling-wine producer, Weibel Vineyards, the last winery pulled up its roots in 1996 for Woodbridge, California.

The end of Fremont’s wine industry may have been inevitable, however, the heritage of wine and wine making in southern Alameda County is not lost. In fact, we in the bay area are surrounded by an amazing wine universe and can be immersed in it if one so desires. One of the many benefits of living in the Bay Area is that we live in close proximity to some of the best wine producing regions in the world. We are also a short day-trip or weekend road trip from some terrific up and coming AVAs.

A must for any one who calls California home is to make a pilgrimage to both Napa and Sonoma. While Napa tasting room fees can be a bit pricey, the wine and the experience are well worth it for any wine lover. Sonoma maybe an ideal destination for someone with a pallet that seeks a wide-range of wine varietals, but Sonoma is not to be mistaken as “second fiddle” to Napa in terms of wine quality. Quite literally Napa and Sonoma are two sides of the same coin, in terms of geography and their impact and influence on the global wine world today.

For those wine lovers who only venture out to Napa and Sonoma, or who maybe inclined to be a bit provincial and loyal to their local wine region, I challenge you to explore our state! A weekend trip north of the bay to the picturesque and remote Anderson Valley is a must. This AVA is home to some terrific Pinot Noirs and amazing aromatic white wines. A weekend trip south to Paso Robles will not disappoint. A new comer to California wine, with most of is wineries having been planted in the 1990’s, this region has some terrific Rhone varietals and a restaurant scene that is unmatched on California’s central coast.

Want to go wine tasting but not interested spending too much time on the road? Well, there are many wine trails in Northern California between the Anderson Valley and Paso Robles that deserve some exploring and can be done on a short day-trip. On the edge of the Bay, from Saratoga along the Highway 9 to Santa Cruz along the Highway 17, awaits some great wines and friendly tasting rooms. The Santa Cruz Mountains AVA offers Pinots, Cabernet Sauvignons, Zinfandels, and some traditional Italian varieties. First and foremost the Ridge Winery on Montebello Road in Cupertino is a pilgrimage all wine lovers must make (watch for bicyclists) . A short drive south of the bay along the 101 is a wine road that is off the tasting room radar for many, but well known for its vineyards is the Arroyo Seco and the Santa Lucia Highlands. While very few of the wineries here have tasting rooms open to the public, these Monterrey County wineries are worth the trip (just call ahead and ask for a private tasting).

Last but not least is the Livermore Valley AVA in the east bay. A quick drive along the 580 or Highway 84 will put you right in the middle of wine country less than an hour from most cities in the Bay Area. Livermore’s wine legacy shadows that of the old Fremont wineries step for step, having similar roots in the Mission era, and floundering through the dual shocks of phylloxera and Prohibition. The persistence of the agricultural industry in Livermore has afforded a future for wine on the eastside of the southern Alameda county foothills. Livermore is simultaneously one of the oldest and youngest AVAs in California. At one time California’s wine industry was centered on Livermore. In fact, wine makers from the Livermore Valley won the United States’ first international gold medal in 1889 at the Paris Exposition, nearly a century before the famed 1976 Judgment of Paris.

Livermore Valley is home to over 50 wineries; the overwhelming majority of them have sprung up in the early 2000’s. This late-bloom makes it even younger than Paso Robles in terms of development. Livermore is slowly emerging as an up and coming region, but is struggling to find an identity. In Livermore one can see the twin of Fremont’s wine legacy that was separated at birth. With Fremont’s wine heritage having long since faded into the annual of history, and Livermore now undergoing a renaissance, soon prone to reclaim the past prophesized by Frank Schoonmaker so many years ago. Some say in each bottle of wine is a story; one can say the same for the vines in the vineyards. California and Bay Area wines, although younger than Europe, have no less of a rich tapestry of history and many stories to be retold. So next time you enjoy a nice bottle of California wine, raise your glass to the local wine history that made it all possible. Cheers!

Sources:

Country Club of Washington Township, 1965, History of Washington Township, Stanford University Press, CA

Singleton, Jill M. “Lost Wineries and Vineyards of Fremont, California.” Museum of Local History. Museum of Local History. Web. 03 June 2011. http://www.museumoflocalhistory.org/pages/wineries.htm

Reichl, Ruth. History in a Glass: Sixty Years of Wine Writing from Gourmet. New York: Modern Library, 2007. Print.